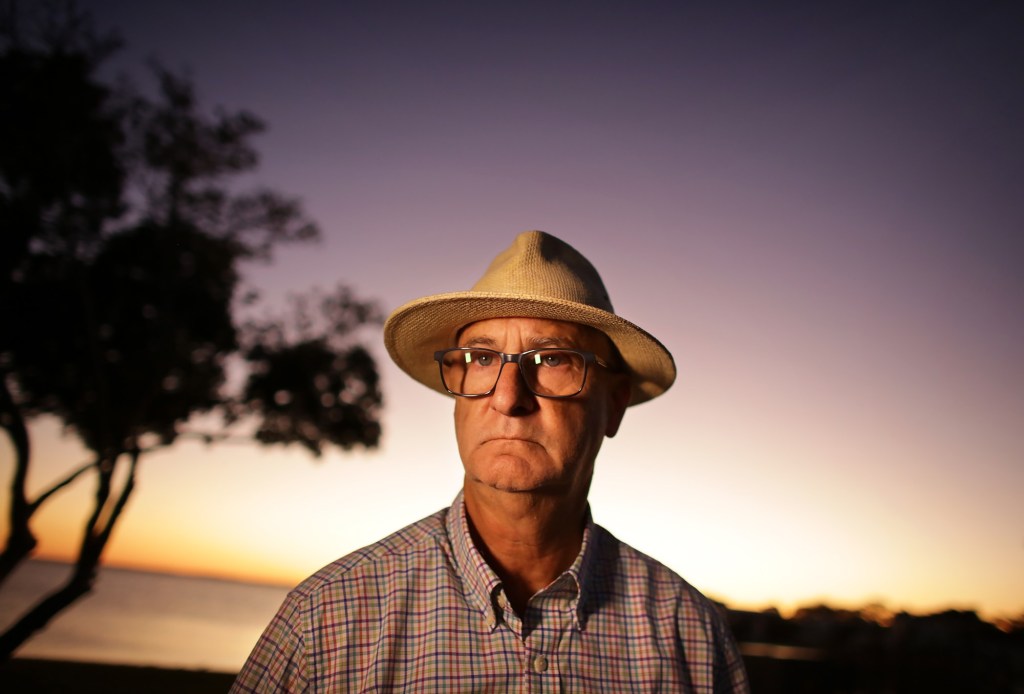

Aharon Andrés Cardona joined the Sodalitium Christianae Vitae as a teenager in Colombia in 1993 because he wanted to help others.

The secretive Catholic society, based in Peru, sought to mold upper-class, fair-skinned boys into “soldiers for God” through a combination of military-style training and theological study.

Cardona said he soon realized, however, that his mission to help others would come with years of physical and psychological abuse.

When he said or did something that his superiors didn’t like, the leader of his community, Daniel Cardó, now the priest of a Colorado parish, punched him repeatedly in the stomach or slapped him in the face, Cardona said in an interview from Colombia.

“He said I needed to act like a man,” he said.

Cardona and his comrades were constantly pushed to their physical limits through running, swimming, squats and pushups. Some threw up or fainted from overexertion, he said. They slept only a few hours a night. Punishments included eating only lettuce and water for days at a time.

“The institution has a logic to humiliate people and to demand from them a lot of obedience,” Cardona said. “They shouldn’t exist anymore.”

Pope Francis made waves in September when he expelled 10 members — including Father Cardó and two others with Colorado ties — from the Sodalitium Christianae Vitae for what the Vatican called “sadistic” abuses of power, authority and spirituality. The pope’s decision rocked the group, which has been under investigation by authorities from Peru and the Vatican, as well as its own leadership, in recent years.

Over the past 25 years, the Sodalitium has established a strong presence in Colorado, where the Archdiocese of Denver entrusted it with a metro-area parish, and where the group has moved several high-ranking leaders along with some of its financial operations.

“All the money is in Denver,” said Paola Ugaz, an investigative reporter in Peru who wrote a book on abuses in the Sodalitium. “Their power is in Denver right now.”

Former members who lived in the Denver community described similar physical and psychological tests in which leaders pushed them beyond their breaking point.

Despite the expulsion from the Sodalitium, Cardó remains a member of the Catholic Church and the pastor at the Holy Name Catholic Church in Sheridan. He declined interview requests for this story, but wrote in an email that he remembers the events with Cardona “very differently.”

“I was never expected or instructed to use violence,” Cardó wrote. “What some have described was not my experience.”

The Archdiocese of Denver, in a statement last month following the Pope’s announcement, defended the expelled members, saying the allegations centered on decades-old claims from South America. Cardó remains a priest in good standing, the Archdiocese said, though he no longer lives with the Sodalitium community on the church’s property.

“Authoritarian direction and control”

Luis Fernando Figari founded the Sodalitium Christianae Vitae, or Sodalitium of Christian Life, in 1971 as a lay community, comprising ordinary members who are not clergy. The group was one of several Catholic societies born as a conservative reaction to the left-leaning liberation theology movement that swept through Latin America, starting in the 1960s.

At its height, the group counted about 20,000 members across South America and the United States, and was approved by Pope John Paul II in 1997. That membership is down to 125 people spread across nine mostly Latin American countries, including six prominent members in Colorado.

As the SCV, as the group is known, grew in size, Figari’s reputation as a highly spiritual, intellectual and charismatic man also grew.

“Figari used his leadership status to have authoritarian direction and control of most Sodalits,” or members, according to a 2017 report commissioned by the group. “He was the most powerful person in the organization and many believed that his words and directives came directly from God. Figari’s personal attributes and authority shaped an environment where young men trusted him as a human being, as well as a spiritual, even fatherly, figure.”

The leader boasted about having supernatural gifts, such as the ability to see images of the Virgin Mary or a flaming sword, the symbol of SCV, the report and ex-members said. He used hypnotism to make aspirants bark like a dog or, he said, reduce a person’s body temperature. He claimed he could read minds.

Figari served as Gerardo Barreto’s spiritual counselor for years. The ex-member, who helped start the Denver Sodalitium community, said it was like having a direct connection with God. Others envied him.

“He is a very smart person, very intelligent, like Hitler,” Barreto said in an interview. “He has a very intuitive way to see people — 99% of people, he gets them at once.”

In the St. Elizabeth of Hungary Church in downtown Denver, where members of a sister society lived, Figari’s picture sat next to the Pope’s, an ex-member said. Community members read his works more than the Bible and sang songs based on his writings.

But this mythical status also led Figari to allegedly perpetuate decades of sexual, physical and spiritual abuses. The 2017 report found Figari and three others sexually abused 19 minors and 10 adults, with most of the abuses happening in the 1980s and 1990s in South America.

Former and current Sodalits described Figari in the report as “narcissistic, paranoid, demeaning, vulgar, vindictive, manipulative, racist, sexist, elitist and obsessed with sexual issues and the sexual orientation of SCV members.”

The Vatican in August expelled Figari following an investigation by the church’s top sex abuse experts. It came nine years after the group’s dealings burst into the open following the publication of the book “Half Monks, Half Soldiers” by a former SCV member, Pedro Salinas, and Ugaz, the Peruvian journalist.

Figari has denied the allegations. He was ordered in 2017 to live apart from the Sodalitium community in Rome and cease all contact with it.

The Sodalitium in recent years has denounced Figari’s behavior, apologized to victims and given reparations to those who were harmed during their time in the group.

“Although each individual is responsible before God and others for their own actions, we recognize that our community has committed abuses and faults that have caused real harm,” the group said in a 2019 statement.

Physical tests

Physical challenges serve as a central component of the SCV’s structure.

Figari modeled the group’s initiation program after movies and TV shows he watched, according to the 2017 report. These physical tests involved swimming in cold ocean waters for hours at a time, running long distances in bad weather and forcing aspirants to do thousands of pushups and sit-ups.

It wasn’t rare for superiors to hit members repeatedly in the abdomen for any slight infraction.

“Physical punishment was part of the deal,” said Eduardo Maura, a former SCV member in South America who now lives in Florida. “You have to be strong. You’re not supposed to show any sign that you’re experiencing physical pain.”

Leaders instituted other punishments, including withholding food and water or forcing members to eat dessert covered in ketchup or mustard. Other discipline came in the form of sleeping on the floor or forcing individuals to stay up all night.

Former member Oscar Osterling recalled, at the age of 18, being woken up at 4 a.m. in Peru and told to undress, leaving only his underwear on.

Figari then asked the teens questions while someone filmed them.

“It was a first step to see if we have some sexual insecurities,” Osterling said in an interview from Peru.

The elevation of suffering has been a part of Christian identity since its beginning, said Christy Cobb, a biblical scholar and associate professor of Christianity at the University of Denver. Texts and even early Christian saints tried to embrace suffering in their lives to mimic the suffering of Jesus Christ, she said.

“This ideology, taken to the extreme, can lead to this kind of abuse,” Cobb said.

Leaders also continually tested the psychological makeup of their members.

Aspirants were told at the beginning of their formation period to detail everything in their lives: their intimate hopes, fears and even sexual histories.

The strategy, ex-members say: Break people down so they become dependent on the Sodalitium.

“This was the first step in the brainwashing,” said Martin Scheuch, a former member in Peru who now lives in Germany. “They make you feel bad, like you are the worst in the world. Then they told us that they have the answer to our problems and we must follow Jesus and obey all the things they tell us.”

Moving operations to Denver

These psychological and physical abuses eventually made their way to Denver, ex-members said.

Since at least the 1990s, Denver’s conservative archbishops have maintained strong relationships with the Sodalitium and their sister societies.

Cardinal James Francis Stafford, then Denver’s archbishop, in 1992 invited the Christian Life Movement to Colorado, its first foray into the United States. Figari founded the group in 1985 as an ecclesial lay movement in which young people live communally in marginalized areas. It’s considered part of the Sodalitium family.

Barreto and his wife were part of the first cohort to come to Denver. Figari was initially reluctant to send priests and consecrated members, he said, so instead they sent two married couples to begin evangelization in the United States.

“Stafford had insisted several times he wanted the Sodalitium to come to his archdiocese,” Barreto said.

The presence of the Sodalitium in the U.S. followed in 2003, when Archbishop Charles J. Chaput, Stafford’s successor in Denver, invited the group to live at Camp St. Malo, a retreat center in Boulder County. (Chaput retired when the more liberal Pope Francis replaced him as archbishop of Philadelphia in 2020. He declined interview requests through an Archdiocese of Philadelphia spokesperson.)

The Archdiocese of Denver asked Cardó in 2007 to serve as the parish’s priest. Three years later, Chaput gave the Holy Name parish in Sheridan to the Sodalitium. Not all parishioners at Holy Name belong to the movement but the parish is led by the group and members of the Sodalitium have a house on parish grounds.

Chaput in 2012 spoke before the general assembly of the Sodalitium, where he lauded the group for its devotion to God.

“God has done something extraordinary through the genius and passion of Luis Fernando (Figari), and also through the zeal of each member of the Sodalitium,” he said, according to Scheuch’s account on his blog. “As a bishop, I have seen the results.”

Chaput later invited the SCV to Philadelphia after he became archbishop there.

One former member of the Marian Community of Reconciliation, a women’s group also founded by Figari, recalled the “indoctrination” she went through when she joined the Denver-based community. The Marian community is considered part of the Sodalitium family and members attended the Holy Name parish together. The group shuttered its Denver community in 2022.

“They try and break you down and teach you to distrust your own thoughts and own view of yourself and the world,” the woman said, speaking on the condition of anonymity because she still has family in the parish. “You start to question everything you know and feel about yourself.”

The SCV preyed upon desperate young people searching for meaning and structure in their lives, said another former member of the Denver community. This individual, speaking on the condition of anonymity in order to protect his career, said he was aimless after his parents divorced. The Sodalitium offered order.

“There was a lot of grooming and manipulation of people who were at risk of joining a cult,” this person said, calling his experience living in the Denver house for a few years in the 2010s “a nightmare.”

As Peruvian and Vatican authorities have zeroed in on the Sodalitium in recent years, it appears the movement has increasingly used Denver as its hub.

Three of the 10 members expelled by the Pope last month had Colorado ties, including the former executive director of the Catholic News Agency, Alejandro Bermudez, and the leader of the Sodalitium’s Denver-based community, Eduardo Regal.

The group has also moved two of its companies to Colorado amid accusations of financial misdealing in Peru.

One of them, the Foundation Santa Rosa, a charity that supports Sodalitium causes around the world, was registered in Colorado in 2016 and used the same address as the Holy Name church. The other, Providential Inc., did not appear in the Colorado Secretary of State Office’s business database, but Ugaz said it is based in the state.

The Sodalitium moved its operations overseas, Ugaz said, because its leaders fear prosecutors in Peru or the Vatican could seize their assets. And Denver served as a perfect place to hide away, she said, due to the group’s close relationships with Chaput and his successor, current Denver Archbishop Samuel J. Aquila.

Aquila is close friends with Bermudez and came to Holy Name for lunch, multiple ex-members of the church told The Post. He also led mass at the Sheridan church, and his photo is prominently featured on the SCV’s website.

“The Sodalitium feel very safe with them,” Ugaz said, referring to the Archdiocese of Denver. “They feel nothing will happen to them there.”

Aquila is not and has never been a member of the SCV, said Kelly Clark, a spokesperson for the Archdiocese of Denver. The archbishop has not served as their confessor and celebrates mass with them a few times a year, she said.

Cardó, who was not mentioned by name in the 2017 report commissioned by the SCV, told The Post in an email that he’s been “devastated” and “deeply saddened” since the Pope’s announcement.

“I joined the Sodalitium because I felt called to serve God and his people through community life and service,” he said. “I am glad I have been able to help others through my vocation as a Catholic priest and I have great respect for the vast majority in the Sodalitium who have toiled to serve others over many years.”

Cardona, the former member who says he was punched by Cardó, said he felt sadness when he heard the Colorado priest had been expelled from the Sodalitium. Cardó, he said, was just doing what the higher-ups expected from him.

“Daniel Cardó is the victim of the rules of the institution,” he said.

But removing 10 members will do nothing, he said.

“It’s better to cancel the whole institution,” Cardona said.

Originally Published: