Most Bay Area residents are finding it harder to afford necessities such as groceries, gas, child care, housing, and home insurance, according to a new poll by the Bay Area News Group and Joint Venture Silicon Valley, with seven in 10 respondents agreeing the region’s quality of life has gotten worse in recent years.

The survey also found that residents are deeply skeptical of Silicon Valley’s tech industry and overwhelmingly support a high-profile November ballot measure to raise penalties for retail theft and drug crimes statewide.

The poll, which surveyed more than 1,650 registered voters across the core five-county Bay Area in August, came after pandemic spikes in inflation, crime and homelessness. While more recent data suggests those trends have mostly slowed or reversed, the poll indicates residents still feel it’s a challenge to call the Bay Area home.

“It’s a demanding place,” said Russell Hancock, president and CEO of Joint Venture Silicon Valley, a regional think tank. “We have a punishing economy.”

For poll respondent Seema Kanani, earning a six-figure salary is still barely enough to support her two teenage children as a single mother. To save money, the clinical social worker has for the past few years lived with her son and daughter, two parents and an adult sister in the same crowded four-bedroom house in Milpitas where she grew up.

Kanani, 45, and her children recently got the keys to a two-bedroom apartment of their own, but she’s anxious about being able to make the $3,600 monthly rent while also shouldering the higher costs of food and gas.

“My income is always going to show above the poverty level, but it’s not going to be enough to sustain us,” she said.

According to the poll, 70% of registered voters said the Bay Area’s quality of life has worsened over the past five years, while just 13% said it has improved. Seventeen percent said it’s stayed the same.

While respondents made their frustrations clear, the percentage who said quality of life had gotten worse was actually 9% lower than when this news organization and Joint Venture asked the same question last year. The polls’ margin of error is about 2.5%.

When asked which issues pose a serious problem for the region, large majorities of respondents agreed that homelessness (97%), housing costs (96%), the cost of living (96%), health care costs (86%), crime (83%) and child care costs (82%) are significant challenges.

Most also agreed that over the past year, it’s become harder to afford food and groceries (79%), utilities (73%), transportation and gas (65%), taxes (64%) and housing (62%).

Whether state and local leaders can find ways to alleviate those concerns and costs could have far-reaching impacts on everything from population and workforce trends to school enrollment and the region’s political climate. With inflation cooling and a more optimistic economic outlook coming into view, the Bay Area appears to be reaching an inflection point in its post-pandemic recovery.

“Now the questions are around how economic growth will take shape over the next five years,” said Jeff Bellisario, executive director of the Bay Area Council Economic Institute, which researches regional economic and policy issues.

Kanani, in Milpitas, said she wants to provide her 15-year-old daughter, Rainah, and 13-year-old son, Veer, more personal space during their high school years. But she worries that signing a lease could mean hard choices about how to set aside money for expenses such as sending Rainah to taekwondo competitions or saving for both teenagers’ college tuitions.

“I might reach a point where I might blow through my savings, and we’ll just see what things look like tomorrow,” she said.

According to the poll, 53% of respondents said they can’t contently afford their monthly expenses and also put money toward saving or investing.

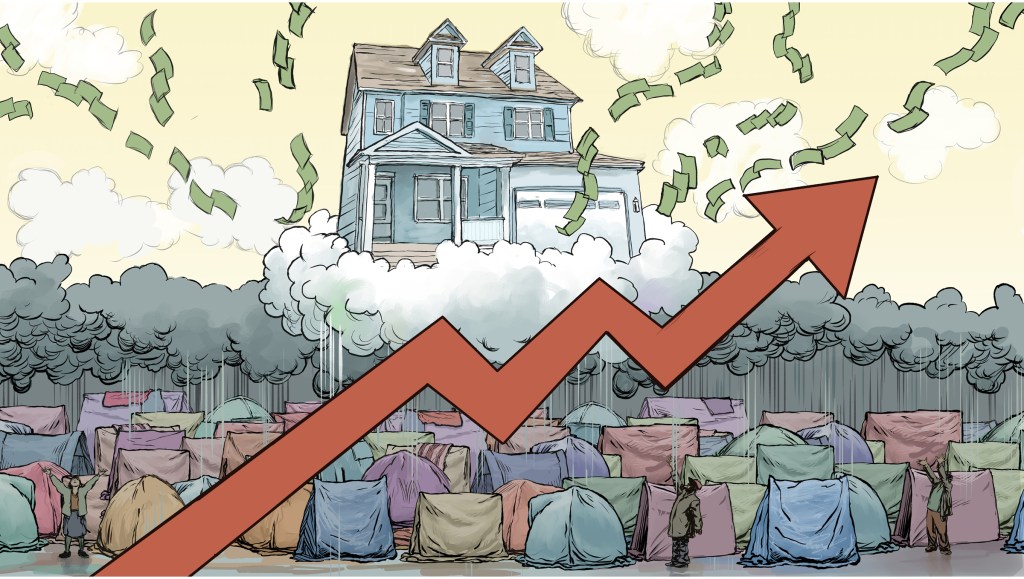

For many Bay Area residents, the most challenging monthly cost is housing. According to census data, about half the region’s renters and a third of local households with a mortgage spend more than 30% of their income on housing, classifying them as cost-burdened by federal standards.

A whopping 46% of respondents said they were likely to leave the Bay Area in the next few years, with two-thirds of those citing high housing costs as the main reason to consider a move. During the pandemic, people fleeing the region contributed to a 3% population drop, though that exodus has since slowed.

To reduce housing costs, tenant advocates have put a measure on the November ballot that would allow cities statewide to significantly expand rent control. Opponents, however, argue it would push rentals off the market and stall new housing construction.

When asked to select ways the region might best be improved, respondents’ top choice at 39% was building more affordable housing. In recent years, state and local governments have adopted a flurry of laws and policies aimed at spurring more affordable and market-rate housing in hopes of reducing costs and homelessness, though high interest rates and other economic headwinds have slowed construction.

Homeowners in the poll also said the state’s home insurance meltdown is hitting their finances. Fifty-two percent said their home insurance premiums have increased significantly, 22% said they have avoided using their home insurance policy out of fear of cancellation or rising rates, 12% said they’ve had a difficult time finding an insurer to write them a policy and 8% said an insurer had canceled a policy.

The state insurance department is now finalizing a plan to persuade providers to cover more homes and cancel fewer policies, but consumer advocates worry it could also mean rate hikes for many Californians.

For parents with young children, the cost of child care is yet another challenge. Sixty-eight percent said the availability of affordable child care in their community was “not too good” or poor.

Across nearly every demographic, a majority of respondents agreed the Bay Area is on the wrong track. The groups saddled with the heaviest burden of the region’s challenges, including low-income earners and people of color, were the most likely to hold a pessimistic view.

But the starkest disparity was between Biden and Trump voters in the 2020 election. Fifty-one percent of Biden voters said the Bay Area is on the wrong track, compared to 93% of Trump voters.

“Look at the four years under Trump. Look at what the price of gas was, interest rates, inflation — look at what they were his last two weeks in office and look at what they are now. It’s outrageous,” said poll respondent Richard Brown, 71, a self-described independent and Trump voter.

Brown, of Alameda, said some of the most shocking price hikes are at the grocery store. “I’ll buy a twelve-pack of paper towels that’s like $16,” he said. “What the heck?”

To prevent spikes in gas prices, state lawmakers are now considering a plan from Gov. Gavin Newsom to force oil refiners to keep minimum fuel reserves, though doing so likely wouldn’t lower overall prices at the pump.

In addition to choosing a new president this November, voters will decide on a statewide ballot measure that aims to roll back decade-old criminal justice reforms and raise penalties for theft and drug crimes. According to the poll, 70% of Bay Area voters are likely to support the measure, dubbed Proposition 36.

Respondent Jorge Ruiz, 41, of Danville, plans to vote for Proposition 36. He said a consignment store and cosmetic shop in his neighborhood have been burglarized multiple times over the past year and stricter penalties would help crack down on property crime.

“I go on Nextdoor, and people think it’s like the wild, wild West now,” Ruiz said.

When it comes to the tech sector, 75% of respondents said the industry wields too much power, and 69% said it’s lost its moral compass. Eighty-one percent agreed it’s the driving force behind the region’s high housing costs.

After a rash of recent layoffs and more than a decade of scandals over data privacy, children’s mental health and outright fraud, fewer residents appear to believe the region’s economic powerhouse is following through on its initial promise to make the world a better place.

“Now people feel like the sector might be filled with villains,” said Joint Venture’s Hancock.

Despite those concerns, Newsom recently vetoed a controversial bill that would have regulated the state’s growing artificial intelligence ecosystem. Even so, state and federal officials are continuing to pursue sweeping antitrust lawsuits aimed at reining in the market dominance of Silicon Valley tech giants Google and Facebook.

In spite of the region’s many challenges, poll respondents still found reason for optimism: 84% said they believed their own lives are headed in the right direction.

And with wages rising faster, unemployment relatively low and the Federal Reserve, signaling victory in its fight against inflation, aiming to lower borrowing costs for everything from mortgages and credit cards to business and construction loans, better days could also be ahead for the broader Bay Area.

But in a region that’s long suffered from a staggering wealth gap, there’s no guarantee everyone will share in the benefits of a speedier recovery, said Bellisario of the economic institute.

“We are coming back, but the question becomes: What does that look like?” he asked. “And what does that look like across a very broad range of households?”

This is the first story in a three-part series.

Coming Monday: Widespread agreement Silicon Valley wields too much power, poll shows

Coming Tuesday: Poll finds broad support for rolling back criminal justice reforms