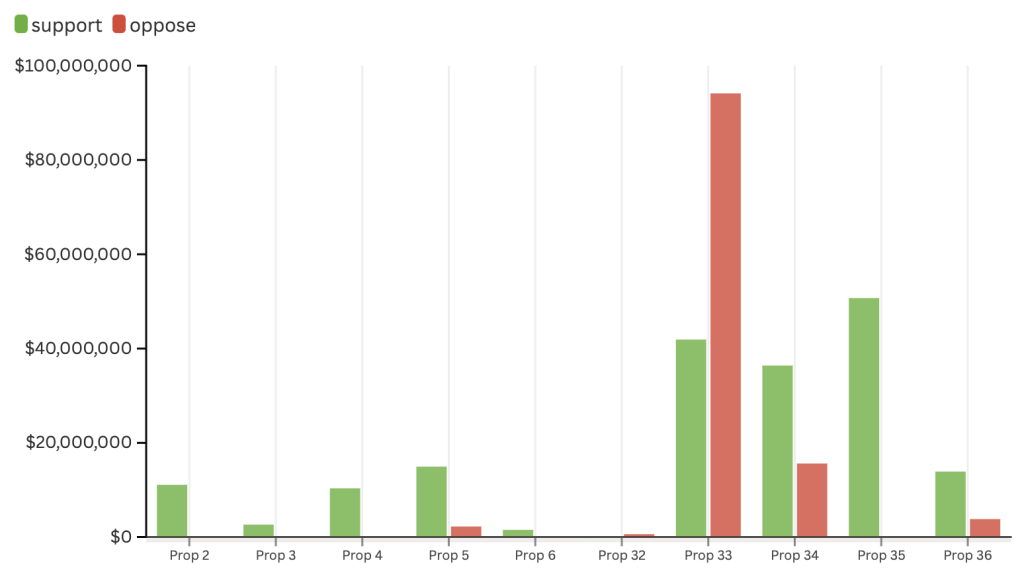

The 10 propositions on the California ballot this year are responsible for a spending frenzy, with campaigns shelling out more than $300 million as they try to get their messaging to voters.

By far the biggest fundraiser this year has been the opposition to Proposition 33, which would allow cities and counties to impose strict rent caps on all types of housing. Through Oct. 19, the end of the pre-election campaign finance reporting period, the main “No on 33” committee had raised $77 million, mostly from the California Apartment Association.

Since then, the Apartment Association has dropped an additional $11.5 million into their committee’s coffers, with “No on Prop. 33” ads warning it could increase housing costs still running on TV and streaming services, with the hope of swaying those who have yet to fill out their ballots.

Those ballots, possibly still hanging out on the kitchen tables of many of California’s 22 million registered voters, include several pages dedicated to the propositions that made it through the Golden State’s complex, century-old direct democracy process.

“We are asking Californians to make decisions on some pretty complex stuff,” said Melissa Michelson, political science professor at Menlo College.

“Political scientists will tell you, direct democracy is hugely popular,” Michelson said, “but it’s not necessarily a good way to make policy, because you can only vote yes or no.”

Ten propositions is an average number to appear on the ballot, but this year’s measures are fighting an uphill battle, “overshadowed by the presidential race because it’s such a contentious one,” according to Shaun Bowler, a political science professor at UC Riverside.

“These policy proposals have got to make their voice heard above all the noise of the presidential race — and boy, that’s difficult,” Bowler said.

The total spent on this year’s propositions doesn’t quite reach the record $357 million online gambling companies and tribal casinos raised for a pair of measures that would have legalized sports betting in the Golden State in 2022.

Before that, the state’s most pricey proposition was Proposition 22 — when Uber, Lyft and DoorDash forked over more than $200 million in 2020 to beat back a state law that would treat their drivers as employees.

At the end of October, the California Secretary of State reported just over 6 million votes had already been cast.

While opposition spending has been twice as high, Proposition 33 also inspired the second-most “Yes” spending, with nearly $42 million spent in support of the proposition through Oct. 19.

Proposition 35 has garnered the most “Yes” spending of any of the measures, with over $50 million spent, and no opposition spending to speak of. The proposition would make permanent a tax that helps pay for Medi-Cal health care services, the state’s Medicaid program that provides health care for low-income Californians.

All together, “it’s an incomprehensibly large amount of money,” Bowler said. “But the task that these campaigns have is telling voters [their message] … and there’s going to be 20 million voters.”

Some of the more complex or specific propositions need to do even more to communicate with voters, and that’s where endorsements from environmental groups or local unions help people decide, according to Bowler.

On the other hand, some propositions, like Proposition 3, are more straightforward — and generate less spending.

Proposition 3 would overturn 2008’s Proposition 8, which defined marriage as between a man and a woman. Since same-sex marriage was legalized in California in 2013, and nationally in 2015, it is more of a symbolic proposition and one where less money has been spent because people already know how they feel.

“If you’ve already made up your mind, and it’s a pretty clear-cut issue, then it doesn’t matter how many ads you get,” Michelson said.